Arms have wicked consequences on the society, they slow down development and do not represent any economic advance. If the same resources allocated for the upkeep of the army and the military industry were set aside for the civil industry, these resources would generate more human and social development.

In addition, arms are one of the main causes of the North-South divide since they contribute to poverty in Third World countries because of the indebtedness caused by the export of arms from North to South countries.

Are there really as many arms as it is said? Are they necessary?

The truth is that there are nuclear and non-nuclear weapons. Among non-nuclear weapons we can distinguish between conventional, which are not arms of mass destruction, biological and chemical ones.

Despite their importance, most of the amassed weapons are not nuclear. Moreover, four fifths of the world military spending are set aside for conventional arms and for the upkeep of armed forces.

A good example of the insecurity created by the excess of arms is that since the end of the Cold War there have been 87 armed conflicts with more than 7 million victims. 90% of these victims were civilians and the arms used were conventional weapons produced in North countries.

How much does it cost to maintain this situation?

On a worldwide scale, military spending continues to be extremely high. For example, it is eighteen times higher than the development assistance that economically developed countries transfer to Third World countries. Besides, they absorb an amount seven times higher than the payments demanded to South countries in services (interests and repayments).

Which is the economic effect of the production of arms?

It is hard to know which kind of good weapons are. They are neither consumption goods (shoes, food…) nor productive goods (tractors, machinery, equipment…). From a strictly economical point of view they are unproductive goods since they do not produce any economic value in spite of the notable costs that they mean; they consume valuable resources (some of them are not renewable) that could be allocated for other purposes.

Nevertheless, they are considered as security or defence goods. But whom do they defend? From whom? How? Who has decided this? When have defensive priorities been decided? Who and how has defined the threats?

On the other hand, negative effects of military investment (opportunity costs) have debilitating consequences for developed countries in the long term that turn to be devastating in the case of Third World countries in the short and middle term. It has been proved that for these countries it leads to disaster; a developing country needs productive investment, education of the workforce, improvements in medical care, communication and transport systems and more and a better equipment. Diverting resources used for the satisfaction of these needs means choosing a strong destructive potential for the economy of the country.

Spain is not an exception. Also here, economic effects bound to the production of arms are negative in the middle and long term.

Does the defence of a country need a powerful military industry?

It is often said that the defence of a country demands a powerful and feasible defence industry with export capacity and vocation. However, we are not told who decides these defensive needs for the country in question. Recent history proves that priorities pointed out by centres of political decision do not coincide with the perceptions of the public opinion: they want to defend us from individuals or nations that we do not consider a threat. Official defence policy usually overvalues military and arms aspects due to the prevailing militarism and it neglects political-diplomatic or economic aspects. The fact is that the lines of argument of the arms industry and the official defence policy always refer to national interest but, strangely, they decide unilaterally what should be understood for national interest.

Is it possible to reach a strictly defensive defence policy? Would it cost less?

Investigation and production of arms work with their own dynamic, following commercial and market criteria. This means that, from a strictly defensive point of vie, neither provocative nor interventionist, unnecessary weapons are produced. It is crystal clear: the main reason for producing arms is not the national interest but reasons bound to economic benefit from companies of this sector. Sometimes national interest curiously coincides with the interest of the businessmen or the military-industrial complex.

A cheaper defence policy can be drawn up by relinquishing all offensive weapons, ten times more expensive on average than the ones oriented to counteract them.

Nevertheless, Spanish government has chosen the opposite way, which is producing all kind of conventional arms through national and international projects. Some of them are unnecessary as the European fighter plane (Eurofighter 2000), Tiger helicopters, F-100 frigates, Leopard tanks and military transport planes A400M. All of these are offensive weapons to transport war to other territories. The explanation is simple: it has been chosen a security policy based on rearmament and military force (not for the national interest) and that implies strengthening national warlike industry.

Is a powerful military industry necessary to avoid external dependence?

It has often been said that the development of a national defence industry allows to drop the purchase of material to other countries and to improve self-sufficiency.

It has also been omitted that the needs of armaments of a country depend on the type of defence chosen and the alliances this country takes part in. In Spain it has been opted for a type of defence that implies necessarily importing arms systems although they could be reduced in the middle term through international co-manufacturing and national manufacturing. It is necessary to repeat once again that many of these weapons would be needless with a non-provocative defence policy.

Furthermore, the independence of a country is not simply based on arms self-sufficiency. In a time when, at least in developed countries, military invasions are not usual, economic, financial and cultural penetration turn to be much more effective.

Does the arms industry create jobs?

Several studies carried out by the United Nations indicate that the same investment in another sector, different from arms industry, would create more jobs since the notable demand of specialization of this sector would be eliminated. But let us examine the Spanish reality more specifically.

Growth rates of industries in this sector have been and are still unequal. Some companies have undergone a marked increase in their sales and exports. Others present important deficits and undergo deep restructuring. The fact is that the predominant tendency is that of promoting companies considered to be capital intensive that consequently need little labour. That is, military technology not only does not create jobs but also makes them drop. Besides, the same investment in a different sector would always produce more.

Is arms export unavoidable?

The truth is that not necessarily. It depends on whether they are produced for security reasons or for export. However, official declarations tend to be circular: arms industry guarantees defence ability and taken into account current prices of military products, the viability of the industry demands to raise the production in order to reduce the costs. Nevertheless, overproduction demands to export.

The fact is that there are industries created according to export rates but not to the satisfaction of needs of the interior market. There are countries where only one fourth or fifth of the production is exported (as Sweden or Germany). On the other hand, there are countries like Italy that export 70% of their production.

Spain (as France and Great Britain) exports between 40% or 50% of the production of the sector, which means that many arms are designed in order to be sold abroad.

Does arms export have a connection with political criteria?

Justifying the export referring to the need of reducing the costs or achieving a return on the effort of investigation and development means forgetting the political nature of defence industry. The whole defence industry is favoured and promoted by the governments, everything enjoys incentives and subsidies and there are laws and regulations regarding exports. We are not talking about the typical industrial sector whose production, no matter how, is usually and principally bought by the state. It is not possible to keep both opposite discourses: whether “there is a need to have arms at our disposal for national security reasons” (regardless of their cost since it has usually been said that security has no price) or “national market for arms will never justify the substantial investments derived from the production of arms”. Trying to maintain both things invalidates both statements. Anyway, exporting to “achieve a return on costs” does not exempt the companies, authorities and citizens from the political responsibility of selling weapons to dictatorships, countries that violate Human Rights or nations at war.

Can arms trade be internationally controlled by means of agreements or treaties?

Theoretically, yes. It is possible to establish agreements between supplier countries to reduce the volume of transfers, to prevent the transfer of some kind of arms or the export to certain countries. Nevertheless, the attempts have been few and they have not been successful. It remains the possibility of limiting and controlling it through agreements of the United Nations or embargos imposed by international organizations. Regarding United Nations, there have been a large number of ideas. In 1978, on the occasion of the 1st Special Session on Disarmament, all the member states promised that the recipients and suppliers would start talks in order to limit conventional arms transfers. Hitherto, it has just been a promise.

Therefore, international agreements, although really desirable, tend not to work due to the lack of clear data on transfers accepted by all the states, to the different economic and politic interests at stake and to the justifications of the governments and companies adducing free sovereignty and the right of free enterprise.

It results, then, essential to encourage controls of production and arms export at a state level.

Can a certain country control the transfers and the exports?

It can. There are, undoubtedly, political, economic, legal and technical difficulties (establishing a clear list of what is understood by “arm”) but, once again, we can do whatever we want to. Countries like Sweden or Austria have done it choosing restrictive policies on their exports. Countries that opt for clearly restrictive politics receive pressure from the military-industrial complex. It is not difficult to hear things like “if we don’t sell them, someone will do it… In fact, it is better if we take advantage of it…” or to resort to influence peddling, bribery and blackmailing. There are countries where arms exports have to be passed by the respective Parliament; others have parliamentary commissions that control the exports to follow triangular operations and underhanded exports through false destination certificates and so on. Spanish politics, despite the current laws, is very permissive.

Are there indirect measures that promote limitations on arms trade?

Yes, indeed, there are. Among others: a) reducing military budgets b) giving saved resources over to development (without accepting that actions like selling trucks for military use to a developing country are considered “development”) c) preventing that arms sales to Third World countries are made with Development Aid Fund loans or soft loans with low interest rates d) initiating a conversion process of war industries into industries that manufacture socially useful goods.

Is it really possible to transform arms industry?

It certainly is. It is not an unfeasible promise. Firstly, there are very elaborate examples and proposals developed in different countries. Secondly, in the case of Spain general criteria in absence of concrete studies coordinated with trade unions are very clear: a) alternative products should essentially make use of the same skills in their production that current workers already have b) alternative products should be produced in the very workplace using already existing factories, assembly lines and material resources with adequate innovations and new investments c) new products should be feasible and necessary, that is, products that can be bought by the public or by the government d) workers should not be transferred e) The whole conversion process would demand a totally and absolutely democratic planning, decision and execution.

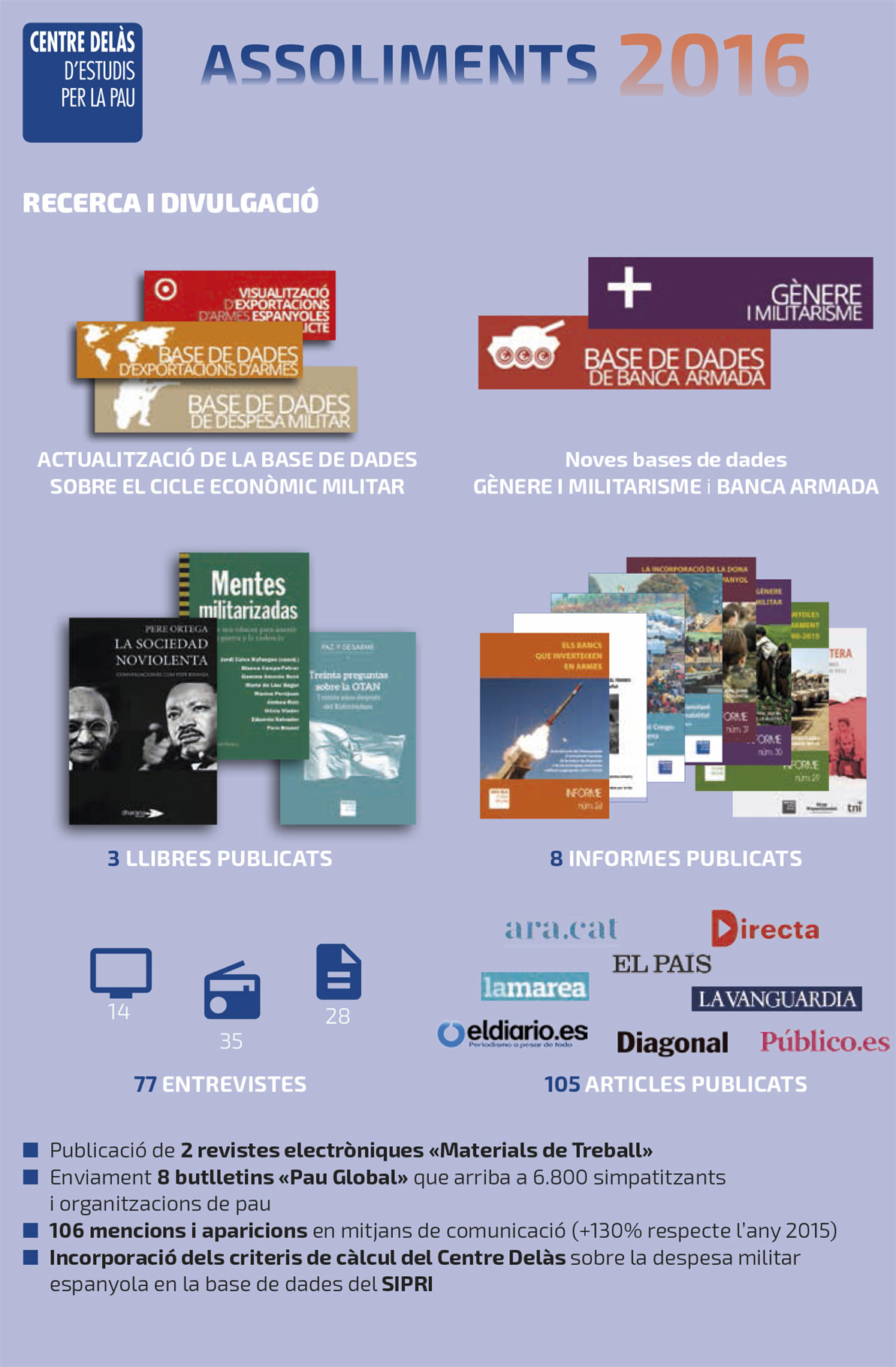

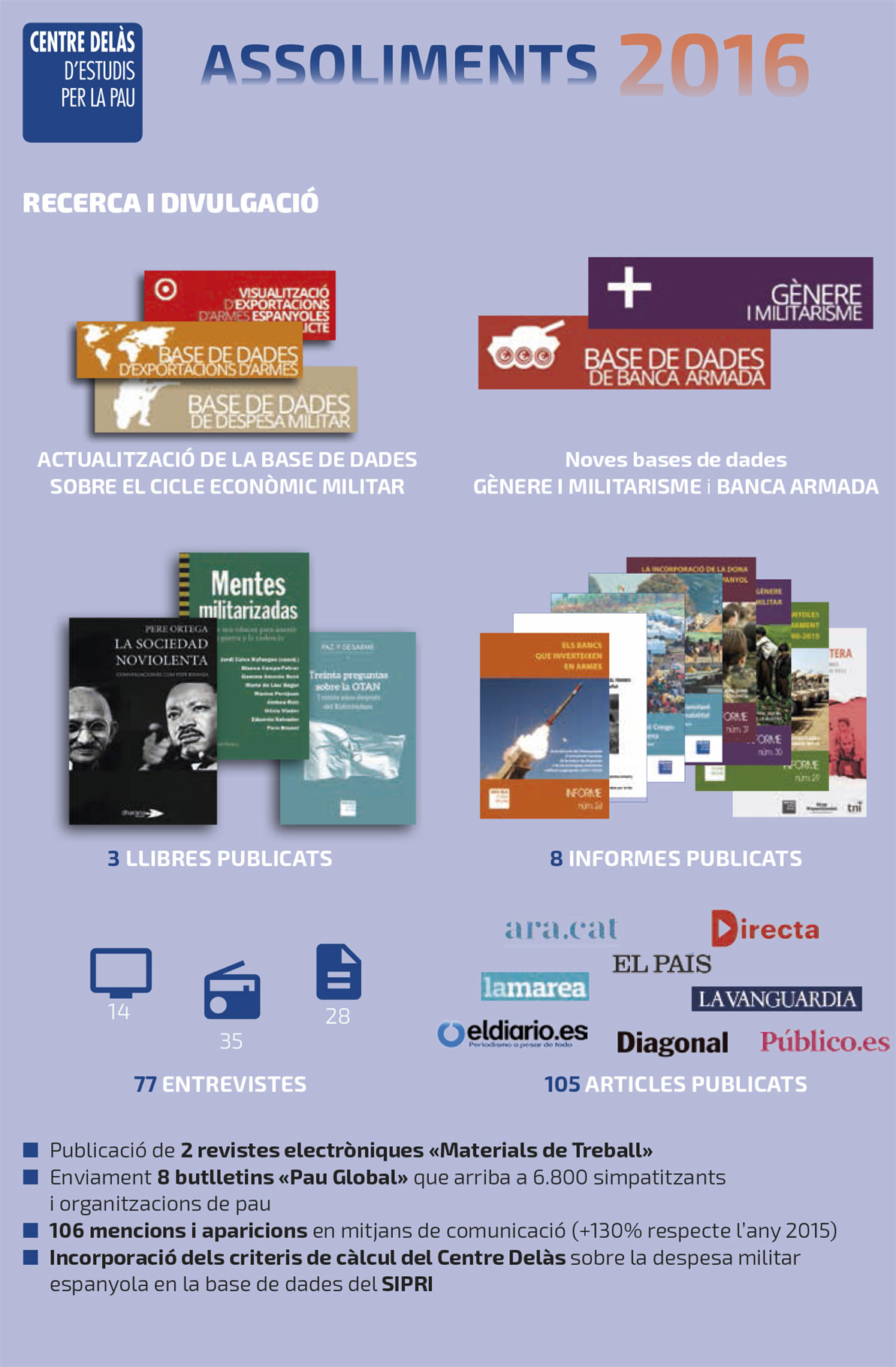

Delàs Center of Studies for Peace's achievements 2016

Delàs Center of Studies for Peace's achievements 2016 Delàs Center of Studies for Peace's achievements 2016

Delàs Center of Studies for Peace's achievements 2016

The Centre d’Estudis per la Pau J.M. Delàs (Study Centre for Peace J.M. Delàs) was created in 1999 in Justícia i Pau (Justice and Peace, as a result of the Campanya Contra el Comerç d’Armes –C3A (Campaign against Arms Trade - C3A) which had started in 1988. Currently, it is an independent Center of Research on issues related to disarmament and peace.

The Centre d’Estudis per la Pau J.M. Delàs (Study Centre for Peace J.M. Delàs) was created in 1999 in Justícia i Pau (Justice and Peace, as a result of the Campanya Contra el Comerç d’Armes –C3A (Campaign against Arms Trade - C3A) which had started in 1988. Currently, it is an independent Center of Research on issues related to disarmament and peace.